Updated July 2020

This factsheet contains information on the following:

- Downy Mildew of Spinach | Lettuce | Kale and other Brassicas

- Powdery Mildew of Kale, other Brassicas, and Lettuce

- Cladosporium Leaf Spot of Spinach

- Botrytis Crown Rot of Lettuce

- Root Rot

Additional Information:

- Downy mildew and powdery mildew of arugula

- If you grow winter greens please complete this survey.

- Summary information from survey responses received in 2018

- What Works for Organic Disease Control in Winter Tunnels

- Presentation on Organic Disease Control in Winter Tunnels at New England Vegetable and Fruit Conference Dec 2019

Introduction

Foliar diseases observed recently in winter greens are of special concern. They include downy mildews (spinach, brassicas and lettuce) and powdery mildews (brassicas and lettuce). All are capable of rendering a crop unmarketable. Plants are susceptible at all stages, including cotyledon stage. Their occurrence in field-grown plants in late fall and in winter tunnels is perplexing because most have not been observed recently in these crops grown during traditional production periods, with the exception of brassica downy mildew. Conditions during production of winter greens evidently are very favorable for these pathogens that tolerate cool temperatures. Prolonged periods of leaf wetness or high humidity likely is a factor. Low light levels and short days mean these pathogens have long periods to produce spores. Plastic covering high tunnels protects the pathogens from exposure to damaging UV radiation.

Occurrence of these foliar diseases appears to be sporadic, reflecting where the pathogen is present and conditions are favorable. This perception is based on reports received so far from growers. Knowledge about disease occurrence is important for developing appropriate, effective management programs. This information is needed to help determine initial sources of inoculum and potential for pathogen survival between crops and spread. If you grow winter greens, regardless of whether or not you have seen any of these diseases, please help by completing the survey.

Early morning is the best time to look for symptoms because foliar pathogens produce spores during nighttime; seeing spores confirms a diagnosis. Long periods of leaf wetness or high humidity promote development of most foliar diseases; powdery mildew being a notable exception. Common management practices for these diseases include selecting resistant varieties when available. Use drip irrigation or overhead irrigate when leaves are dry and afterwards promote rapid drying with fans. It is especially important to make sure leaves are dry after watering before placing row cover over plants. Vent high tunnels as often as temperature permits; but realize when open while field-grown crops are present, spores can move outside from an infected crop inside and vice versa. Foliar diseases are difficult to control with fungicides in leafy vegetables because of low tolerance for diseased tissue, especially when applications are started after symptoms are seen. Fungicides do not have the capability to cure diseased tissue. Thorough coverage is particularly important with organic fungicides as most have contact activity and cannot move through leaves as conventional fungicides can. Destroy diseased leaf tissue promptly after the crop is finished. Physically remove this tissue from tunnels when feasible to minimize potential for the pathogen to remain.

Downy Mildew of Spinach

There can be a long delay between infection and symptom appearance when conditions are unfavorable following infection. Downy mildew can seem to explode overnight when conditions become favorable again. The initial sources of the pathogen for recent occurrences of downy mildew in the region are not known.

Symptoms

Purplish-gray, fuzzy growth of the pathogen, which is usually on the underside of leaves, is diagnostic. Early morning is the best time to see as the growth (which is spores and the structures holding them) is produced overnight, and during the day spores are dispersed by air currents. On the top side of leaves, opposite where the growth develops, the leaf tissue will be yellow, initially dull becoming brighter and larger with time. Subsequently affected tissue will become dry and tan. If only leaf yellowing is seen, which could occur when humidity is low, put suspect leaves upside down on wet paper towel in a closed ziplock bag for a day. Keep the bag in the dark, such as inside a box, to further promote the pathogen if present to develop.

Management

1. Select varieties with resistance to at least races 12 and 14. These races were identified associated with recent cases in the northeast that were tested. This is the most important management practice. There are varieties with resistance to 16 of the 17 races described so far, but seed is limited, in high demand, and thus more expensive than seed of other varieties.

2. Use production practices that minimize leaf wetness and reduce humidity. When using row covers, do not place over wet plants. Some occurrences of downy mildew in high tunnels have been associated with covering spinach when leaves were wet from watering.

3. Locate spring spinach transplants and crops as far away as possible from high tunnel spinach crops.

4. Rotate out of land where spinach was grown for at least 2-3 years. The pathogen can survive a few years in soil as oospores. Oospores can be produced when both mating types (equivalent of gender) of the pathogen are present together infecting a leaf. This spore type is the result of sexual reproduction. Oospores also could be left behind in soil after planting contaminated seed. Oospores are not dispersed by wind as occurs with sporangia, which are the asexually-produced spores on the underside of leaves.

5. Check plants carefully for symptoms at least once a week. Conditions during spring become more favorable as temperature and humidity increase.

6. For crops not managed organically, apply fungicides preventively or at first symptom. Conventional fungicides permitted used in greenhouses include Actigard, Aliette, ProPhyt and other phosphorous acid fungicides, Ranman, Revus, and Tanos). Organic products tested in university experiments have been ineffective or not adequately effective for commercial production. See report Downy Mildew Developing in Spinach in Northeastern U.S.

- Labeled products include copper, Actinovate, Double Nickel, LifeGard, Regalia, Oxidate, Trilogy, and Zonix. Copper is considered most effective based on limited evaluations conducted. Check REI and PHI when selecting conventional or organic fungicides to make sure fits production schedule.

7. Report suspect occurrences promptly to your state extension specialist so that we can keep everyone generally aware of occurrence in the region, samples can be submitted for race identification to guide variety recommendations, and we can improve our knowledge about this disease.

8. Destroy spinach crop if symptoms continue to develop despite management practices or right after final harvest even if no downy mildew seen. It is important to control the amount of inoculum in the region to minimize opportunities for spread and keep downy mildew impact low.

Hot water seed treatment is unfortunately not expected to work for this downy mildew pathogen because it contaminates the seed as oospores, which are pretty tough structures. They are likely imbedded in the seed coat making them difficult to physically remove. Additionally, there is not solid evidence that oospores on seed serve as a source of inoculum.

Note that while leaves are held in plastic bag after harvest, affected leaves may rot and new symptoms may develop, especially if there is residual moisture from washing.

Other Susceptible Plants

The pathogen, Peronospora farinosa f. sp. spinaciae, is only known to infect spinach. It is possible some related (Chenopodium) weed species are susceptible to some races. However, cross infection experiments conducted to date have not been successful: pathogen taken from spinach did not infect any weeds and pathogen from weeds did not infect spinach.

Pathogen Sources

Possible initial sources of the pathogen for the northeast region are wind-dispersed spores (sporangia) from affected crops outside the region, infected spinach produce from outside the region, or oospores on contaminated seed. Spinach with downy mildew has been observed for retail sale.

Favorable Conditions

Cool with long periods of leaf wetness or high humidity. Wet foliage is especially favorable. Optimal temperature range for this pathogen is 59 – 70 F. However, spores of the downy mildew pathogen have been observed on plants over a very wide temperature range, from freezing (frozen plants) to 118 F!

Based on observations from growers, conditions in high tunnels in the middle of winter are not very favorable for downy mildew (perhaps too cold) except during long periods of leaf wetness (such as when row cover put over wet plants). Varieties bred to be resistance to downy mildew can be very effective when resistance includes the pathogen race present. Past spring occurrences were promptly destroyed, thus the pathogen did not have much opportunity to spread. Some downy mildew pathogens have demonstrated ability to spread well via wind-dispersed spores. The cucurbit downy mildew pathogen in the eastern U.S. starts in southern Florida and spreads at least as far north as Long Island every year (occurrences in upstate New York and New England may result from spores dispersed from the mid-west). The basil downy mildew pathogen has been found on single, isolated plant in a landscape planting. Sources of the pathogen for the recent occurrences of spinach downy mildew have not been identified.

More information and photographs: Spinach Downy Mildew

Downy Mildew of Lettuce

Symptoms

Initial symptom on upper leaf surface is typically light green to yellow areas, often angular in shape being bounded by major veins. Diagnostic white fluffy growth of the pathogen develops typically on the lower surface under these lesions, but can occur on the upper surface (especially when affected leaves are bagged and refrigerated) and can be present more generally on the lower surface similar to powdery mildew. Early in infection only spores may be present. Affected tissue eventually turns brown. Older leaves often are affected first. View photo gallery at Downy mildew on lettuce.

Disease cycle

Potential initial sources of the pathogen include spores dispersed by wind from other lettuce plantings, plant debris when previous lettuce crop was affected, and contaminated seed; however, the risk of infection from contaminated seed is not known. Downy mildew pathogens have narrow host ranges (the one affecting lettuce is not the same as the one on spinach) and they are obligate pathogens, meaning they need living host tissue to survive unless they are able to produce a specialized spore (oospore), which requires presence of two strains of the pathogen of opposite mating types because oospores are the result of sexual reproduction.

Management

- Select resistant varieties.

- Conventional fungicides labeled for this disease that can be applied in greenhouses include: Actigard, Aliette, ProPhyt and other phosphorous acid fungicides, Ranman, Revus, and Tanos.

- Organic fungicides include copper (check label as some products are not permitted used in greenhouses), Actinovate, Cease, Double Nickel, LifeGard, Oxidate, Regalia, Serenade, Sonata, Timorex Gold, Trilogy, and Zonix.

Downy Mildew of Kale and Other Brassicas

While all brassica crop types are susceptible, downy mildew may not develop in all crops being grown on a farm because of host specialization in the pathogen. This disease develops when temperature is 46-61F at night and below 75 during day.

Symptoms

Leaf spots can develop that are similar to those in lettuce being yellow and bordered by large veins with white downy pathogen growth on the leaf underside. Spots can also be less defined. Sometimes within affected tissue black irregular lines form that have been described as lace-like. This is characteristic for downy mildew. Symptoms vary among brassica crop types. Photographs on seedlings are posted here. In addition to leaf symptoms in winter greens, broccoli and cauliflower heads can be infected which predisposes them to bacterial rot. A resulting symptom of systemic infection is dark discoloration of vascular tissue that can extend into heads. taproots of turnip and radish

Disease cycle

Sources of the pathogen include contaminated seed, plants surviving overwinter, sexual spores (oospores) in debris, and wind-blown asexual spores. Other hosts, in particular cruciferous weeds, can play an important role in the disease cycle. Oospores in soil can infect roots leading to systemic infection of plants.

Management

- Select pathogen free seed.

- Inspect plants routinely for symptoms.

- Minimize leaf wetness and high humidity.

- Physically remove affected crop debris after an outbreak when feasible or destroy it.

- Fungicides listed for lettuce are labeled for use on brassicas except Tanos.

Powdery Mildews of Kale, other Brassicas, and Lettuce

Symptoms

Characteristic superficial white growth of the pathogen develops on both leaf surfaces. It develops a powdery appearance when the pathogen produces spores. Leaves can quickly become covered with the powdery growth.

Disease cycle

Powdery mildew pathogens have narrow host ranges, thus different pathogens cause powdery mildew in kale and lettuce. Also similar to the downy mildew pathogens, they are obligate pathogens. But in contrast, they do not need long periods of leaf wetness or high humidity to develop, and in fact develop best under dry conditions. Kale is more commonly affected than other brassica crops as a result of variation in susceptibility and/or physiological specialization in the pathogen.

Management

Organic fungicides listed above for downy mildew in lettuce and kale are also labeled for powdery mildews in these crops with the exception of Zonix. Other fungicides include sulfur, JMS Stylet-oil and other mineral oils, and MilStop and other potassium bicarbonates.

Lettuce varieties exhibit differences in susceptibility (2018 research report)

Cladosporium Leaf Spot of Spinach

Symptoms

Spots caused by this fungal pathogen are round, small (up to 1 cm in diameter) and tan with green fungal growth (mostly spores) eventually developing in the center. This growth distinguishes this disease from anthracnose and Stemphylium leaf spot.

Disease cycle

This pathogen can be seedborne. Its spores are dispersed by wind and splashing water. Cool, moist conditions are favorable.

Management

- Treat seed with hot-water or bleach.

- Use drip irrigation.

- There are no conventional or organic fungicides labeled specifically for this disease that are permitted used in a greenhouse.

- Select less susceptible varieties. Growers have reported observing variation in severity. There are no varieties bred to be resistant to Cladosporium. Gazelle, Kolibri, Kookaburra, and red veined varieties were seen to be highly susceptible.

Botrytis Crown Rot of Lettuce

Please report if you see to further our knowledge about occurrence and importance of this disease in the Northeast. There have been very few confirmed occurrences.

Additional images are at the bottom of this page.

Symptoms

This disease starts with infection of old leaves that are damaged or senescing and are touching the soil. Affected tissue initially looks water-soaked, then becomes brownish-gray to brownish-orange as a soft wet rot develops. Next the pathogen infects the healthy crown area where the stem is in contact with soil. This tissue turns brownish-orange and eventually can become completely rotten causing the plant to wilt and collapse. Characteristic fuzzy gray to brown pathogen growth covering diseased areas, especially basal leaf tissue, is diagnostic and distinguishes this disease from others that result in plant death such as white mold (aka lettuce drop). Also, roots are not affected with Botrytis crown rot. Black sclerotia may form on diseased tissue. They are flat and smaller than those occurring with white mold.

Disease cycle

The causal pathogen, Botrytis cinerea, is very common and has a large host range. This fungus produces a spore dispersed by wind, usually in abundance which gives infected tissue a gray to brown fuzzy appearance. With all host plants it typically starts developing on dead or injured plant tissue, gaining energy to be able to infect healthy living plant tissue. Botrytis cinerea also produces sclerotia which enable the pathogen to survive for years in soil. Optimum temperature range for growth of this pathogen is 70 – 77 F; however, it is capable of growing over a wide temperature range (28 – 90 F) with growth being very slow at the extremes.

Management

- Minimize damage to plants from cultivating and other farming practices.

- Over-grown lettuce transplants are more susceptible because they are more likely to be damaged during planting than small seedlings.

- Keep humidity in the plant canopy low, ideally below 85% RH. In particular, adjust watering to avoid long periods that the soil surface is wet. Use drip rather than overhead irrigation to minimize leaf wetness.

- Remove dead plant tissue from the tunnel during the growing season if feasible, and also remove plant debris promptly after last harvest.

Root Rot

Several pathogens able to survive in soil can infect roots. These pathogens do not need living plant tissue to survive, and have much wider host ranges than the mildew pathogens. Pythium is likely the most common affecting winter greens because cold, wet soils are favorable for its development. Typical symptom of root rot caused by Pythium is the outer cortex sloughed off revealing the root’s white center.

Management

- Manage irrigation to avoid soils becoming saturated and remaining wet for long periods.

- Biopesticides labeled for root rotting pathogens include Actinovate, Bio-Tam, Double Nickel, Promax, RootShield, Serenade, Taegro and SoilGard.

Please Note: The specific directions on pesticide labels must be adhered to — they supersede these recommendations, if there is a conflict. Check labels for use restrictions. Any reference to commercial products, trade or brand names is for information only; no endorsement is intended.

Additional images – Botrytis Crown Rot of Lettuce

Following three images taken by Teresa Rusinek, March 2021, show the pathogen’s spores (conidia) which are the abundant gray fungal growth on the crown tissue, its sclerotia which are the black structures in the crown tissue in the second image, and the devastating impact it can have on a lettuce crop.

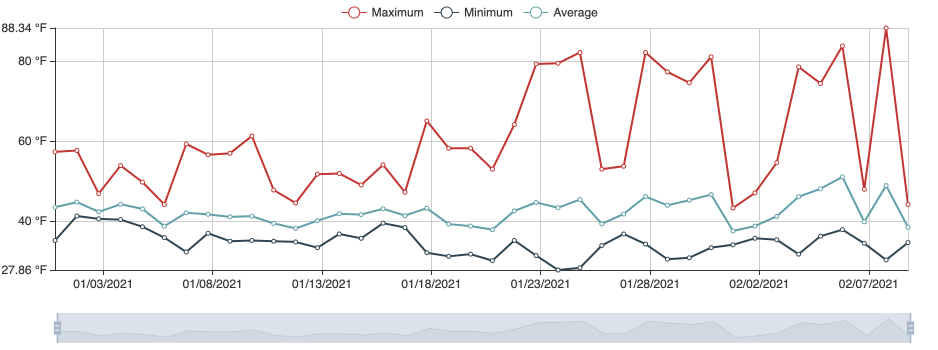

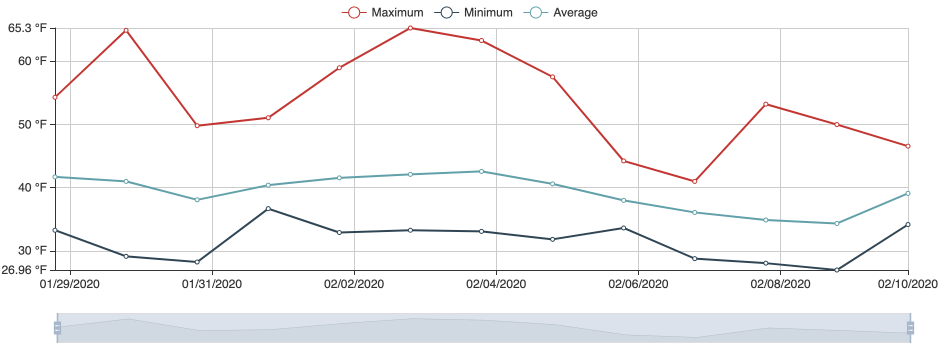

Following images and temperature records are from a grower in February 2021. The temperature records document that it was much warmer in 2021 reaching optimum range for the causal pathogen, which could account for crown rot developing in 2021.

More information/prepared by:

Margaret Tuttle McGrath

Associate Professor Emeritus

Long Island Horticultural Research and Extension Center (LIHREC)

Plant Pathology and Plant-Microbe Biology Section

School of Integrative Plant Science

College of Agriculture and Life Sciences

Cornell University

mtm3@cornell.edu