Potato scab is a common tuber disease that occurs throughout the potato growing regions of the world. Although scab does not usually affect total yields, significant economic losses result from reduced marketability of the tubers. Economic losses are greatest when tubers intended for table stock are infected, since appearance is important for this market. While superficial scab lesions do not greatly affect the marketability of processing potatoes, deep-pitted lesions, however, do increase peeling losses and detract from the appearance of the processed product. The occurrence of scab and its severity varies by season and from field to field. Cropping history, soil moisture, and soil texture are largely responsible for this variability. Potato scab lesions can be confused with powdery scab, a disease caused by an entirely different pathogen, the fungus Spongospora subterranea. (See Detection of Potato Tuber Diseases and Defects.)

Symptoms and Signs

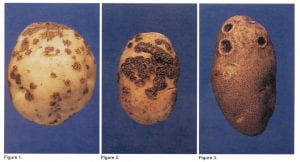

Potato scab lesions are quite variable and distinctions have been made between russet (superficial corky tissue), erumpent (a raised corky area), and pitted (a shallow-to-deep hole) scab as depicted in Figures 1, 2, and 3 below. All of these can be caused by the same pathogen, Streptomyces scabies; however, the type of lesion probably is determined by host resistance, aggressiveness of the pathogen strain, time of infection, and environmental conditions.

Individual scab lesions are circular but may coalesce into large scabby areas. Insects may be involved in creating deep pitted lesions. The term “common scab” generally refers to the response of the disease to soil pH. Common scab is controlled or greatly suppressed at soil pH levels of 5.2 or lower. Common scab is widespread and is caused by S. scabies. “Acid scab” seems to have a more limited distribution, but has been found in several states in the Northeast. This disease occurs in soils below pH 5.2, as well as at higher levels. The causal agent, S. acidiscabies, is closely related to the common scab pathogen and can grow in soils as low as pH 4.0. Acid scab is controlled by crop rotation, but can be a problem when seed is produced in contaminated soils. Acid scab lesions are similar, if not identical, to those caused by S. scabies.

Disease Cycle

Most if not all potato soils have a resident population of S. scabies which will increase with successive potato or other host crops. Scab-susceptible potato varieties appear to increase soil populations faster than scab-resistant varieties. Rotation with grains or other nonhosts eventually reduces but does not eliminate the S. scabies population. This pathogen is a good saprophyte and probably reproduces to some extent on organic material in the soil. Given the right environmental conditions and a scab-susceptible potato variety, scab can occur in afield that has been out of potatoes for several years.

S. scabies infects young developing tubers through the lenticels and occasionally through wounds. Initial infections result in superficial reddish-brown spots on the surface of tubers. As the tubers grow, lesions expand, becoming corky and necrotic. The pathogen sporulates in the lesion, and some of these spores are shed into the soil or reinfest soil when cull potatoes are left in the field. The pathogen survives in lesions on tubers in storage, but the disease does not spread or increase in severity. Inoculum from infected seed tubers can produce disease on progeny tubers the next season.

The disease cycle of S. acidiscabies is similar to that of S. scabies, but the acid scab pathogen does not survive in soil as well as common scab. Inoculum on seed tubers, even those without visible lesions, seems to be important in disease outbreaks in New York.

Factors Influencing Disease Severity

- Varietal resistance. Though the mechanism of resistance to scab is not well understood, varieties with different levels of resistance have been identified through field screening programs. Using resistant varieties is an effective tool for management of scab. Resistant varieties are not immune, however, and will become infected given high inoculum densities and favorable environmental conditions. The limited information available indicates that there is a good correlation between resistance to common scab and to acid scab among potato varieties. Superior is the standard for resistance in the Northeast. Other resistant varieties include Keuka Gold, Lehigh, Pike, and Marcy. Varieties that are moderately resistant include Chieftain, Eva, Reba, Andover, and Russet Burbank.

- Soil acidity. Severity of common scab is significantly reduced in soils with pH levels of 5.2 and below, but losses can rapidly increase with small increases in pH above 5.2. Potatoes are commonly grown in soils with a pH of 5.0 to 5.2 for control of common scab. As mentioned, S. acidiscabies (“acid scab”) causes scab in low-pH soils. This species does not compete well with other soilborne microbes, however, and can usually be controlled with seed treatments and crop rotation. While low-pH soils provide good control of common scab, there are disadvantages associated with this management strategy. Plant nutrients are most available at soil pH levels near 6.5. Since acid soils are unfavorable for most vegetable and field crops, the number of them that can be grown in rotation with potatoes is limited. Maintaining soils near pH 5.0 reduces both fertilizer efficiency and minor element availability, and may result in phytotoxic levels of some minor elements. Potatoes grown in soils near pH 6.5 produce higher yields with less fertilizer. Lack of crop rotation aggravates many pest problems, especially the Colorado potato beetle.

- Soil moisture. Soil moisture during tuberization has a dramatic effect on common scab infection. Maintaining soil at moisture levels above -0.4 bars (near field capacity) during the 2 to 6 weeks following tuber initiation will inhibit infection by S. scabies. Bacteria that flourish at high soil moisture appear to outcompete S. scabies on the tuber surface. However, maintaining high soil moisture may be difficult in some soils, and it is possible that other disease problems may be aggravated by excessive irrigation.

- Soil type and soil amendments. Light-textured soils and those with high levels of organic matter are favorable to scab infection. Streptomyces are generally involved in the decomposition of soil organic matter, and therefore thought to be stimulated by its presence. Applying manure to potato fields can cause an increase in scab infection. Coarse-textured soils are conducive to scab, probably because of their moisture-holding capacity; thus, gravelly or eroded areas of fields that tend to dry out rapidly are often sites of heavy scab infection.

- Crop rotation. Crop rotation reduces the inoculum levels in potato fields, but S. scabies can survive for many years in the absence of potato. This may be due to saprophytic activity or an ability of S. scabies to infect other plants. Infection of seedlings of many vegetables and fleshy roots of beet, cabbage, carrot, radish, spinach, turnips and other plants has been reported. Rotation with small grains, corn, or alfalfa appears to reduce disease in subsequent potato crops. Red clover, however, stimulates problems with common scab and should not be used in fields where scab has been a problem. S. acidiscabies appears to have a host range similar to that of S. scabies but does not survive well in the presence of nonhost crops.

Recommended Disease-Control Strategies

- Use resistant varieties in fields where scab is a problem.

- Use scab-free seed and seed treatments to prevent introduction of the pathogen into fields. Seed treatments do not eliminate the pathogen but will provide some suppression of disease. Consult current potato disease-control recommendations for appropriate seed treatments. For labeled seed treatments see current Cornell Integrated Crop and Pest Management Guidelines for Commercial Vegetable Production.

- Rotate heavily infested fields away from potatoes and alternate hosts such as radish, beets, and carrots. Use small grains, corn, or alfalfa in rotations; avoid red clover.

- Maintain soil pH levels between 5.0 and 5.2 by using acid-producing fertilizers such as ammonium sulphate. Avoid or limit the use of such alkaline-producing amendments as lime and manure.

- Avoid moisture stress during the 2 to 6 weeks following tuberization.

More information/prepared by:

Originally created by Rosemary Loria for Vegetable MD Online. Updated April 2021 by:

Margaret Tuttle McGrath

Associate Professor Emeritus

Long Island Horticultural Research and Extension Center (LIHREC)

Plant Pathology and Plant-Microbe Biology Section

School of Integrative Plant Science

College of Agriculture and Life Sciences

Cornell University

mtm3@cornell.edu